Transfusion Medicine and Sickle Cell Disease

Introduction

Blood provides a mechanism by which nutrients, gases, and wastes can be transported throughout the body. It consists of a number of cells suspended in a fluid medium known as plasma. Serum refers to plasma after clotting factors and fibrin have been removed.

Hemoglobin Structure

Normal hemoglobin (Hgb) is a complex structure. The primary structure contains amino acids strung together to make a polypeptide globin chain. These globin chains are arranged into helices, forming the secondary structure. The tertiary structure consists of coiled globin chains forming pockets that bind heme; each heme molecule, containing one ferrous iron (Fe2+) molecule, is synthesized in the mitochondria and cytosol of erythroid precursors. Four globin chains then bind to form the final quarternary structure of Hgb, which is a tetramer.

Sickle Cell

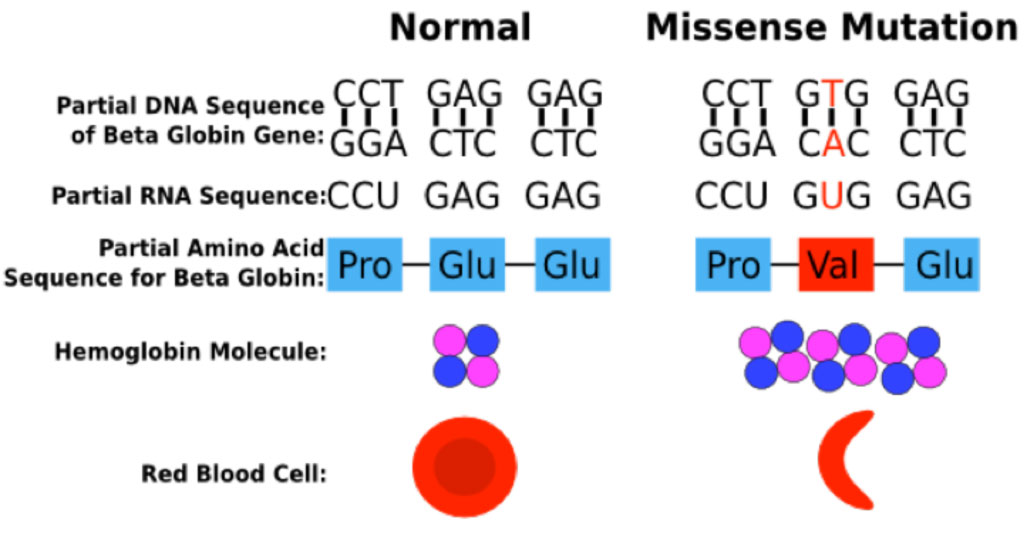

Hemoglobin abnormalities arise when there is a mutation or deletion involving a portion of one of the globin genes. Sickle hemoglobin (Hgb S) results from a point mutation in the beta globin gene at position 6, in which the normal glutamate is replaced by valine.

The Hgb S mutation generates a Hgb molecule with reduced solubility upon deoxygenation. Insoluble Hgb S polymerizes within circulating red blood cells. The polymerization of Hgb S causes dehydration of the red blood cell, leading to a dense intracellular concentration of Hgb S polymers, further enhancing Hgb S polymerization. These changes lead to a distortion in the shape of the red blood cell and a decrease in cell deformability, ultimately resulting in sickling of the red cell.

Polymerization of Hgb S

As red cells traverse the microcirculation, oxygenated hemoglobin releases its oxygen, generating deoxygenated hemoglobin. In patients with Hgb S, the deoxygenated form of Hgb S bears a conformational change in which the β subunits move away from each other, and a hydrophobic patch at the site of the β6valine replacement binds to a complementary hydrophobic site on a β subunit of another hemoglobin tetramer, forming a Hgb S polymer. As deoxygenated Hgb S polymerizes, the red cell is distorted into an elongated banana or "sickle" shape.

Diagnosing Sickle Cell Disease

The laboratory diagnosis of sickle cell disease relies upon hemoglobin electrophoresis to identify the presence of an abnormal Hgb S protein. The hemoglobin electrophoresis in patients with homozygous Hgb S disease typically shows 90-95% Hgb S, 4-5% hemoglobin A2 (Hgb A2), and 0% hemoglobin A (Hgb A).

By contrast, the hemoglobin electrophoresis in patients with Hgb S trait typically shows about 60% Hgb A, 35% Hgb S, and 3-5% Hgb A2.

Transfusion to Treat Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell trait is generally a clinically silent disorder, while sickle cell disease is associated with a number of complications that arise primarily from vaso-occlusion the microvasculature by sickled red blood cells. Clinical manifestations include acute chest syndrome, stroke, pain crises, leg ulcers, nephropathy, priapism, and pulmonary hypertension. Transfusion of wild-type packed red blood cells (PRBC) can treat or prevent many of the complications of this disorder but carries its own set of complications, including alloimmunization against red cell antigens and transfusional iron overload. Red cell exchange transfusions are indicated in acute chest syndrome but may be logistically difficult to perform as they require placement of specialized intravenous catheters. Hydroxyurea, a chemotherapy agent, has become a mainstay of long-term management of sickle cell disease; it induces increased expression of Hgb F, lessening the extent of deoxygenation within red cells, thereby decreasing the number and severity of pain crises.

Type and Screen Test

Identification of red blood cells for transfusion requires performing a "type and screen". The "typing" process enables determination of ABO blood type and Rh(D) restriction. The patient's red blood cells are incubated with serum known to contain antibodies against A, B, or Rh(D) antigens ("antiserum"); red blood cell agglutination to a specific antiserum indicates that the red cells bear that antigen.

Antibody Screen Test

The "antibody screen" evaluates for the presence of antibodies in the patient's serum. Antibody screening is essentially an indirect Coombs test in which a patient's plasma is incubated with a panel of reagent red blood cells expressing various antigen combinations. Should the plasma contain an antibody against one of these antigens, agglutination will occur. Patients requiring transfusions would then be transfused with PRBC lacking those antigens.

Direct Anticoagulant Test

The direct anticoagulant test (DAT), or direct Coombs, is a different type of assay that tests for the presence of alloantibodies or autoantibodies located on the red cell surface. A patient's red blood cells that are coated with either IgG or IgM antibodies are incubated with anti-human globulin (AHG) with specificity against IgG or complement protein C3, the latter of which is fixed by IgM. Red cell agglutination in the presence of anti-IgG AHG indicates that the red blood cells are coated with an IgG-fixing antibody; this may be seen as a consequence of hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn due to maternal-fetal incompatibility to Rh(D), or as a consequence of autoantibodies in a specific type of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) known as warm AIHA, which can arise from exposure to certain medications or in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Red cell agglutination in the presence of anti-C3 AHG indicates that the cells are coated with a complement-fixing IgM antibody, which may occur in cold AIHA (as seen in the wake of some infectious such as infectious mononucleosis or Mycoplasma pneumonia (a.k.a. "walking pneumonia")). Note that while warm AIHA is almost always IgG-fixing and can sometimes be C3-fixing as well, cold AIHA is typically only C3-fixing.