Cell Communication

Learning Objectives

- Students should be able to distinguish between paracrine and endocrine signaling

- Students should be able to describe how steroids alter gene expression

- Students should be able to diagram how receptors activate heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins

- Students should be able to diagram how tyrosine kinases recruit proteins to the cell membrane

- Students should be able to describe how adenlyl cylases and phospholipase C lead to changes in cell behavior

- Students should be able to describe how cells turn off activated signaling pathways

Introduction

Cell communication allows one cell to change the behavior of another cell. Cells communicate using a language that is detected by cells and generates a response. The response usually involves a change in one or more biochemical pathways that alter the behavior of a cell. Cells use the same mechanisms to detect changes in their external environment and respond appropriately.

Cell Communication Language

The language of cells consists of a variety of different molecules that differ in size and chemical composition. Some are hydrophilic: amino acids and their derivatives, proteins and peptides. These molecules must bind a receptor in the cell membrane. Other molecules are hydrophobic: gases and steroids. These can readily diffuse across the cell membrane and interact with intracellular receptors.

Interpretation of Cellular Language

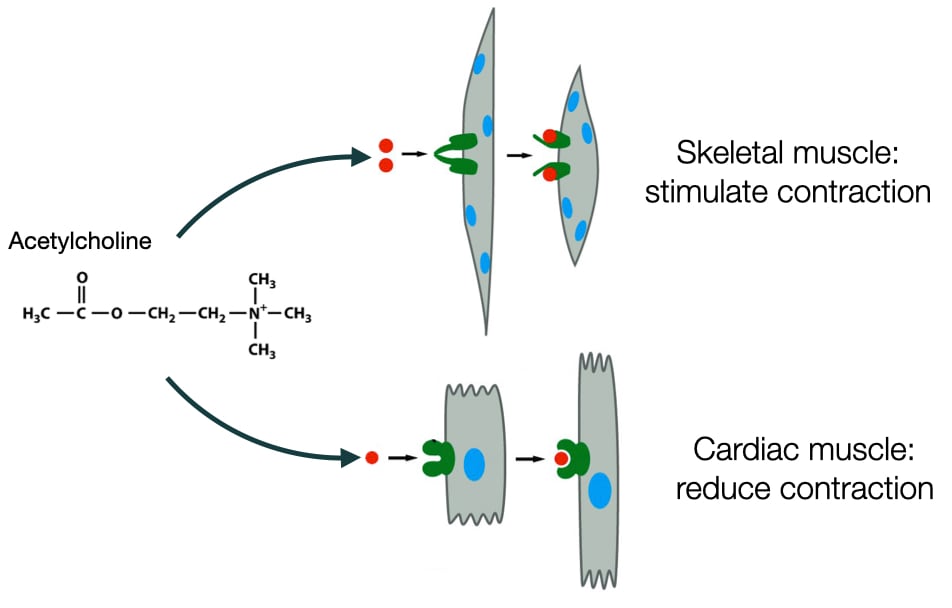

Much like our words, the molecules that mediate cell communication can be interpreted differently by different types of cells. The same molecule can stimulate different responses depending on the type of cell. For example, acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter that stimulates contraction in skeletal muscle, but in cardiac muscle cells acetylcholine decreases the rate of contraction. The difference between skeletal and cardiac muscle cells is in how they are wired biochemically to respond to acetylcholine.

In addition, one molecule can elicit different responses in different tissues or organs to produces an integrated response in the body. For example, epinephrine affects cells in a variety of organs and tissues to produce a flight or fight response in an organism. Cells respond differently to epinephrine depending on which organ or tissue they reside. The biochemical wiring in these cells differs to produce to different responses to epinephrine.

Fast and Slow Responses in Cell Communication

The response of a cell to a signaling molecule can take different lengths of times. A fast response is achieved by altering the activities of existing proteins that alter the rates of specific biochemical pathways leading to a change in cell behavior. The response is fast because the signaling event acts directly on machinery that controls shape or metabolism. Fast responses are usually reversible as once the signaling molecule is removed the activities of the cell's proteins returns to normal.

Cells also respond to signaling molecules by altering gene expression to produce more or less of specific proteins. This response is slow because it requires time to accumulate enough protein to cause a change in cell behavior. The slow response often generates long-term changes in cells such as differentiation into a specific type of cell.

Type of Cell Communication

Communication between cells can be classified based on the distance over which the communication takes place.

Paracrine signaling

In paracrine signaling, the signal released by one cell affects cells only in the surrounding area. Importantly, the signaling molecule does not enter blood stream. The extra cellular matrix that surrounds the cells restricts the diffusion and concentration of the signaling molecule. A special type of paracrine signaling is autocrine in which the cell that produces the signaling molecule also responds to that signaling molecule.

Endocrine Signaling

Endocrine signaling involves cells located at different parts of an organism. Signaling molecules secreted by one cell enter blood stream and travel through blood stream to other parts of body. Cells throughout the body have an opportunity to detect and respond to the signaling molecule. Signaling molecules in endocrine signaling are called hormones.

Signaling Through Direct Contact

A third type of signaling involves direct interaction between cells. Proteins in the cell membranes of different cells can bind each other and the interaction between these proteins can alter cell behavior. For example, a T-cell uses its receptor to recognize antigen on the surface of antigen presenting cell. Another form of this type of signaling is the communication between neurons and their target cells. Neurons make contact with their target cell. Neurons donŐt communicate via these contacts, but they release neurotransmitter at these contact points to affect their target cell.

Strength of Interaction Between Receptor and Signaling Molecule

The different types of signaling differ in the strength of interaction between the signaling molecule and the receptor for that molecule. In endocrine signaling, the hormones are present at low concentration because they are distributed throughout the body. In addition, cells are often bathed in a variety of different hormones and other signaling molecules. Thus, the receptors on cells have to distinguish between several different molecules at low concentration. This requires a high affinity interaction between the receptor and its hormone.

In paracrine signaling or signaling via neurons, the signaling molecule is usually present at higher concentration and is sometimes the only signaling molecule present (neurotransmission). Consequently, the strength of the interaction between the receptor and its signaling molecule is usually lower than in endocrine signaling.

Mechanisms of Detecting and Responding to Signaling Molecules

Cell Communication by Steroids

Steroids are hydrophobic molecules that can diffuse across the cell membrane. The receptors for steroids are transcription factors. Some of these receptors are kept in the cytosol by a chaperone that hides the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) in the receptor. When the receptor binds steroid, it releases the chaperone, exposing the NLS. Once imported into the nucleus, the receptor can activate transcription.

How Steroids Alter Cell Behavior

Steroids alter cell behavior through two rounds of transcription. As mentioned, steroids bind their receptors which are transcription factors. These transcription factors, when bound to steroid, increase the expression of a set of genes called primary response genes. The primary response genes encode proteins that function as transcription factors. Some these transcription factor increases the expression of a set of genes called secondary response genes. These genes encode proteins that alter cell behavior. Some of the transcription factors encoded by the primary response genes inhibit the expression of the primary response genes. This is an example of negative feedback. Thus, steroids not only lead to the activation of genes that change cell behavior but also genes that decrease a cell's response to the steroid.

Cell Communication via Ion Channels

Some receptors are ion channel; often called ligand-gated ion channels. In the absence of ligand (signaling molecule), the channel is closed. When bound to the ligand, the channel opens allowing the ion to move down its electrochemical gradient. These channels often produce depolarize the cell membrane to trigger a change in cell behavior. The acetylcholine receptor on skeletal muscle is an example of a ligand-gated ion channel.

Signal Transduction

Many cell communication events involve extensive processing of the signal produce by a molecule binding to its receptor.

Cell Membrane Receptors

Signaling molecules act via protein receptors in the cell membrane. Receptors contain binding site for a specific small molecule, which is also called a ligand, and another domain that interacts with downstream machinery. Ligand binding induces conformational change in the receptor that activates or inactivates downstream machinery.

Downstream Effectors of Cell Membrane Receptors

Several components relay the binding state of the receptor to the cell machinery (metabolism, gene expression, morphology). Two of the most common components are GTP-binding proteins and kinases. Both function as switches that transmit the ligand-binding state of the receptor to the other components in the signal transduction pathway.

GTP-binding Proteins

GTP-binding proteins are example of biochemical switch. The protein is inactive when bound to GDP and active when bound to GTP. When in its active state, a GTP-binding protein can active a specific biochemical pathway. To convert between these states, GTP-binding proteins rely on two proteins. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) catalyze the release of GDP allowing the protein to bind GTP. GEFs turn on GTP-binding proteins. In contrast, GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) increases the rate of GTP hydrolysis in GTP-binding proteins converting them to the GDP-bound or off state.

Kinases

Kinases are another common component of signaling pathways. Kinases add phosphate groups to proteins. The presence of phosphate will alter the activity, stability and/or location of the protein. The phosphorylation of proteins will alter specific biochemical pathways. Phosphatases remove phosphate groups from proteins.

Signal Transduction Pathways

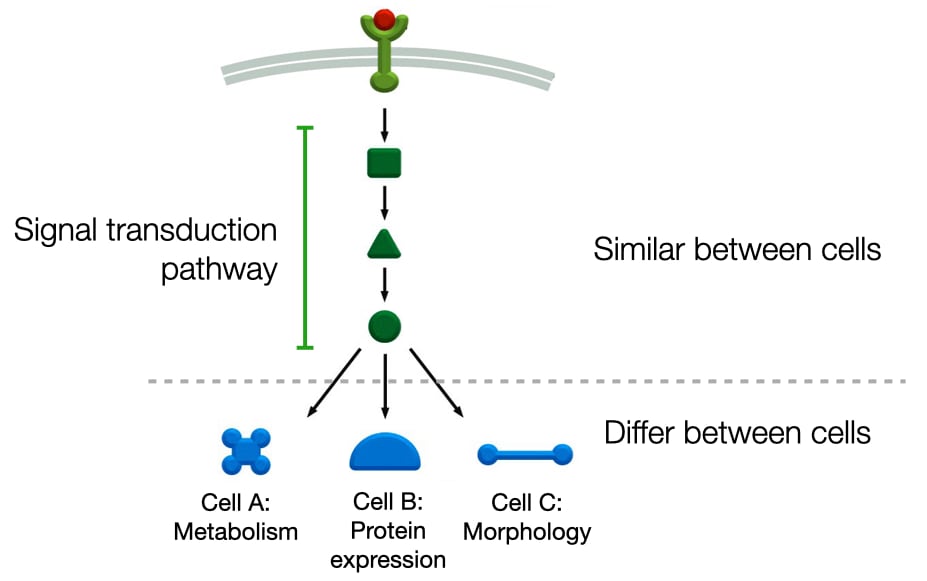

Most pathways will involve several components between the receptor and the biochemical pathways that are altered when the receptor binds its ligand. Cells will often use the same signal transduction pathway to detect ligands but connect those pathways to different cellular processes, such as metabolism, gene expression and cell morphology. This allows different types of cells to generate different responses to the same ligand.

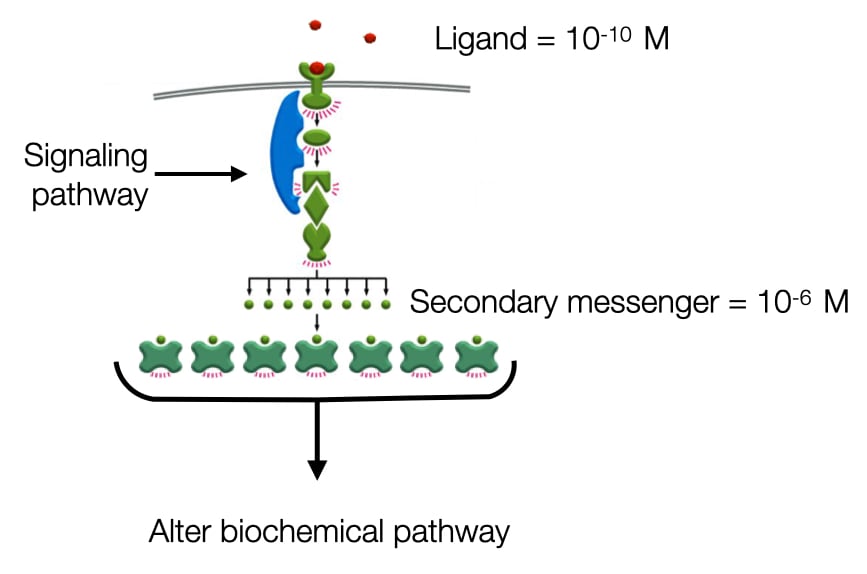

Amplification of Signals

One benefit of having many components between signaling molecule and cell machinery is it allows for amplification of signal. Many signaling molecules are present at low concentration (e.g. 10-10 M). Cells contain only ~1000 receptors for a given ligand but they need to activate hundreds of thousands or millions of proteins to alter cell behavior. To amplify the signal, transduction pathways will activate enzymes each of which produces many copies of a specific molecule. This molecule is known as a secondary messenger and is present at much higher concentration than the original ligand.

Positive and Negative Feedback

Signaling pathways can also regulate their own strength through positive and negative feedback. Positive feedback occurs when a downstream component in a signal transduction pathway increases the strength of the pathway by increasing the activity of an upstream component. For example, a receptor leads to the activation of an enzyme by phosphorylating the enzyme. In positive feedback, the enzyme increases the rate of its phosphorylation to produce more active enzyme. In pathways that use positive feedback, the response to a signaling molecule can become independent of the presence of a ligand because once the pathway is activated, it becomes self-sustaining through positive feedback.

In negative feedback, the downstream component decreases the activity of an upstream component to decrease the strength of the pathway. For example, an active enzyme could alter the pathway to slow the rate at which the pathway produces active enzyme. Negative feedback is used more often in signaling pathways because it allows cells to control the strength of its response to an external ligand. Negative feedback can also produce a variety of patterns in the strength of a pathway, such as oscillation.

Inactivating Receptors

In addition to responding to ligands, cells also regulate the strength and duration of their response to a ligand. If a cell's response to a ligand is too strong or remains active for too long, the cell can become damaged. In some instances, this can lead to cell death. Therefore, signaling pathways will usually trigger reactions that reduce the strength of a cell's response to a ligand (negative feedback). These reactions will often reduce the number of receptors in the plasma membrane or prevent the receptor from activating a cellular response.

Type of Signaling Pathways

Although there are many different signal transduction pathways, there are a few very common pathways. One involves heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins and the other uses cell membrane proteins called receptor tyrosine kinases.

Heterotrimeric GTP-binding Proteins

Heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins contain 3 subunits. The alpha subunit binds and hydrolyzes GTP. The beta and gamma subunits keep the alpha subunit in an inactive state. Heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins usually associate with membranes via hydrophobic tails attached to C-termini of the alpha and gamma subunits. When the alpha subunit binds GTP, it dissociates from beta-gamma subunits. The freed alpha is the main effector of downstream events, but the beta-gamma may also activate some signaling events.

Activation of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins usually occurs via 7 transmembrane receptors which span the cell membrane 7 times. Upon binding ligand, the receptor undergoes a conformational change that activates a domain that functions as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF). The GEF domain catalyzes nucleotide exchange on an associated G alpha subunit, leading to an alpha subunit bound to GTP. In GTP-binding state alpha factor and beta-gamma dissociate and activate downstream proteins.

Adenylyl Cyclase

One of the major downstream effectors of G alpha subunits is adenylyl cyclase. Adenylyl cyclase is plasma-membrane bound protein that catalyzes the conversion of ATP in cyclic AMP. It increases the cytoplasmic concentration of cAMP 20 fold in a few seconds. cAMP is secondary message that will trigger further downstream signaling events. Some G alpha subunits inhibit adenylyl cyclase to turn down production of cAMP.

Protein Kinase A

Most of the effects of increased cAMP are mediated by protein kinase A. Protein kinase A is tetramer of two catalytic subunits and two regulatory subunits. The regulatory subunits inhibit activity of catalytic. cAMP binds regulatory subunits and causes them to dissociate from the catalytic subunits. Once freed, the catalytic subunits are active and can phosphorylate target proteins. Protein kinase A has many downstream targets. For example in some cells, it actives glycogen phosphorylase that breaks down glycogen while inactivating the enzyme glycogen synthase. In other cells protein kinase A phosphorylates the transcription factor CREB that binds to DNA and activates transcription of specific genes.

Phosphodiesterase

Cells must turn off signals to prevent over activation. Cells express a consistent level of phosphodiesterase that converts cAMP into 5'-AMP and keeps cytosolic concentrations of cAMP at a low level in resting cells. Activation of receptor increases activity of adenylyl cyclase and the production of cAMP overwhelms phosphodiesterase to increase cAMP. When adenylyl cyclase is turned off, phosphodiesterase returns cAMP levels to normal.

Signaling via Phospholipids

Phospholipids are also players in signal transduction pathways. Cell membranes contain a variety of phospholipids and the class of lipids called phosphatidylinositols have a prominent role in cell signaling pathways. There are a variety of phosphatidylinositols which have differ by the number and location of phosphates on the inositol group. Proteins in the cell can differentiate between the different phosphatidylinositols.

Phospholipase C

Another downstream effector of trimeric G proteins is phospholipase C. Phospholipase C is an enzyme that cleaves the head groups from phosphatidylinositols. Phospholipase C cleaves the head group phosphatidylinositol 4,5-phosphate to produce diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-1,4,5 triphosphate (IP3).

IP3 and Protein Kinase C

IP3 diffuses to ER where it binds IP3 receptors. Binding to IP3 opens IP3 channels releasing calcium into the cytosol. DAG stays in the membrane and activates protein kinase C. Protein kinase C binds calcium and diffuses to the cell membrane where it also binds DAG. When bound to both protein kinase C and calcium, protein kinase C is active. Protein kinase C has many cellular targets, and there are different classes of protein kinase C with different targets.

Receptor Tyrosine Kinases

Receptor tyrosine kinase are integral membrane proteins that contain a cytoplasmic kinase domain in addition to an extracellular domain that binds ligand. Receptor tyrosine kinases are inactive in the absence of ligand because they are monomers that don't interact with targets efficiently. When bound to ligand the receptors dimerize. Dimerization allows the kinase domain in one receptor to phosphorylate its partner receptor and vice versa.

Recruitment of Proteins

The phosphorylated C-tails of receptor tyrosine kinases are recognized by different downstream signaling proteins. These proteins have domains that recognize portion of the receptor and a phosphate. The phosphorylated receptor brings together proteins in common signaling pathway. In the absence of phosphorylated receptor, enzymes and substrates are at low concentration in cytosol and the reactions are very inefficient. Clustering them on the receptor increases local concentration accelerating the reaction.

Recruitment to the Cell Membrane

Receptor tyrosine kinases can also change the phospholipid composition of the cell membrane to recruit specific proteins. For example a phosphorylated receptor binds PI3 kinase. Binding of PI3 kinase leads to its activation and brings it closer to its substrates phosphoinositol 4,5-phosphate in the cell membrane PI3 kinase phosphorylates PI45 to convert it to PI345. PI345 is recognized by class of proteins with PH domains. Two kinases with PH domains are recruited to the cell membrane by PI345. One kinase phosphorylates the other leading to the activation of the second kinase. The second kinase can now activate its downstream targets. The phosphorylation event proceeds very slowly in the cytosol because both kinases are present at low concentrations. When bound to the cell membrane, the local concentration of both proteins increases, accelerating the phosphorylation reaction.

MAP Kinase Pathways

Another common downstream pathway for tyrosine kinases are the MAP (Mitogen-Activated Pathway) kinases. This pathway is often activated by growth factors. Map kinase pathways contain a set of three kinases. At the top is MAP kinase kinase kinase that phosphorylates and activates MAP kinase kinase. MAP kinase kinase phosphorylates and activates MAP kinase which then phosphorylates variety of target proteins and regulates their activities.

In the image above, MAP kinase kinase kinase is activated by a small GTP binding protein called Ras. Ras is activate when bound to GTP and is often activated by receptor tyrosine kinases in the following steps:

- Activated receptor cross-phosphorylates

- Phosphorylated receptor is recognized by adapter protein

- The adpator protein recruits a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Ras

- GEF catalyzes exchange of GDP for GTP in Ras leading to its activation of MAP kinase kinase kinase.

Decreasing the Strength of Signal Transduction Pathways

If signal transduction pathways are active for too long, cells become damaged and eventually undergo apoptosis. For receptor that bind tightly to their ligand, cells often have to degrade the receptor to turn off the signaling reactions. Receptors are endocytosed into clathrin coated pits. After clathrin is removed, membrane surrounding vesicle undergoes invagination to form internal vesicles that contain receptors. The multi vesicular body will fuse with the lysosome where the receptor is degraded.

An alternative mechanism to decrease the strength of a signal transduction pathway is to prevent the receptor from activating the downstream components in its pathway. This can be achieved by masking the portion of the receptor that activates those components. Often signal transduction pathways will not only alter specific biochemical pathways but also activate proteins that decrease the strength of the pathway. In the image below, the signal transduction pathway activates a kinase that phosphorylates the receptor which had turned on the signal transduction pathway.